The more you know about your horse’s vision, the better partner you’ll be.

Why?

Most of us don’t give horses enough credit and responsibility for what they see and how they deal with it, according to several experts. The result is often more equipment and more head restraint, effectively stripping the horse’s use of this incredible, innate ability.

First, an equine optics primer, from The Mind of the Horse, by Michel-Antoine Leblanc:

- Horses have the largest eyes of all land mammals. Their eyes are about eight times bigger than human eyes.

- They have a large, nearly circular field of vision with two small blind spots – right in front of their nose and directly behind them. The horse will check the blind spots by moving its head, thus compensating for this vulnerability.

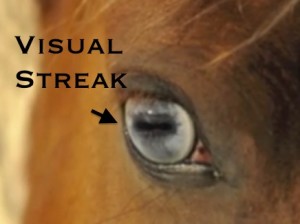

- Given the visual streak of their eye structure, they see in an ultra-panoramic format. If we had an extra pair of eyes positioned near our ears, we’d have that, too. See images for human versus horse perspective. Also, note their limited color spectrum.

Academic research and empirical evidence suggest restraining horses’ heads with rein pressure or mechanical means (martingales or tie-downs) is precisely the wrong thing to do when encountering tricky footing or obstacles.

“Humans cannot extrapolate with any confidence what we see with our own eyes to what the horses see,” writes Leblanc. “Slight poll flexion enables both eyes to see the shape and irregularities of the terrain before it. Small sideways or vertical movements of the head adjust the animals’ vision to take in more of the environment, as needed.”

“Humans cannot extrapolate with any confidence what we see with our own eyes to what the horses see,” writes Leblanc. “Slight poll flexion enables both eyes to see the shape and irregularities of the terrain before it. Small sideways or vertical movements of the head adjust the animals’ vision to take in more of the environment, as needed.”

Leblanc suggests that riders who run steeplechase and jump would be particularly ill-advised to restrict their horses’ heads.

Read more about vision in the new book, Horse Head.

Ross Knox, Randy Rieman, and Martin Black together have more than a hundred years experience working with horses and mules. They spoke to the question of head restraint, especially as it applies to rough or unpredictable footing.

A protégé of Bill Dorrance, Randy Rieman has logged countless miles in rugged country, including years in New Mexico, Hawaii, and Montana (which he now calls home). He spoke between clinic stints in Michigan and Europe.

“I like to let a horse rearrange his head to get better views of the landscape. I give him the liberty to do that. How they feel, posture-wise, is more important than how we feel. Our safety depends on their comfort.”

Years ago, when working with less nimble or athletic horses, Rieman and his friend, Bryan Neubert had a solution: they set them to traveling in a prairie dog town, where the ground was treacherously full of holes.

“It increased their motivation for self preservation. It was super-helpful to turn that responsibility over to the horse,” Rieman said.

“If you continuously hold onto the horse [by rein contact], all the rider information is rendered meaningless. Let the horse balance by dropping the reins, even if it doesn’t fit the right picture in the rider’s mind.”

Ross Knox has logged some 40,000 miles as a Grand Canyon packer. That’s more than anyone. For years, he led equines along the incredibly narrow trails to the Phantom Ranch, a historic oasis at the bottom of the canyon.

He spoke from his home in Midpines, California:

“All true horsemen are going to say the same thing as far as head restriction of any kind. Stay off the face. The horse knows where his feet are coming down better than you do.”

Martin Black, a fifth generation horseman and co-author of Evidence-Based Horsemanship, spoke to the pitfalls of too much head restriction:

“As we rein our horses, it’s likely for them to feel the need for their head to come up, to maintain their balance and in defense of themselves. Typically

when the horse becomes suspicious and worried, the rider becomes worried and takes more control (which again brings their head up), which alters their vision, and the problem perpetuates.”

Additional exercises and ideas related to vision and negotiating difficult areas:

- Whether through pasturing or riding, the horsemen recommended turning a horse onto rugged country for it to learn greater agility.

“Nothing is more underrated than turning a horse out to rough country. They’ll use their feet so much better,” said Knox. “It’s another part of training and you don’t have to be on them to do it.”

- Not all horses are equal.

Recognize your horse’s limitations in confirmation and temperament. A big Belgian might not be your best choice for that Grand Canyon trek. Nor would a high-powered, cow-bred horse.

- If you find yourself in a precarious spot, get off:

“If I did not trust the horse to stay on the trail, I would get off and lead them or do training exercises to help them learn the importance of where to put their feet. But I would be very careful about distracting the horse by taking their attention off the trail and toward me,” said Black.

Mighty night vision:

Read color and night vision article

In experiments, horses could identify black shapes on white background in areas where the darkness was comparable to a moonless night. (Humans fared much worse.)

“It is only when the dark is almost total as in a dense forest with a moonless sky, that they lose their ability to distinguish objects, although even then, they can still navigate familiar surroundings,” writes Leblanc.

But don’t expect this kind of performance if you’ve just taken them from a well-lit barn. It takes 30 minutes for them to adjust and gain night vision. Horses also struggle with shadows and abrupt changes in light.

Read more about vision in the new book, Horse Head.

Watch this video on how we believe the horse sees.

very instructive

In the photos of horse vs human vision, I noticed that the human vision is not in the center of what the horse sees. Could you explain this?

Thanks, Christie. Not too sure of what you mean, but horses see out of the left eye nearly to the left haunches and to the right eye, the same. They have binocular vision straight ahead, monocular vision to left and right. We do not have nearly the peripheral vision as they do. But we don’t have the blind spot in front of our noses like they do. Hope this helps!

Is it true that horses do not have depth perception? In other words I was told a horse will / could fall off a cliff or into a ditch without guidance from the rider.

Hi Julie,

Thanks for your comment! Horses do great as long as you do not restrict their head! They WILL struggle and perhaps panic if you do not let them do this. As Ross Knox said, “They do not go around with a suicide note in their pocket.” These accomplished horsemen say over and over that most horse troubles in hazardous places have everything to do with Operator Error. The ONLY area where they may struggle is going from shadowed to bright and vice versa.

Two eyes are needed to have a clear perception of depth. That’s why 3D images consist of two similar images overlapped.

Therefore I suppose that a cliff to the side may not be noticed so easily, as it will be seen mostly with a single eye. I think it’s best to ask the horse to face the cliff in front of its head to make sure he sees the danger with both eyes.

This is a very informative article. I ride with so many folks that feel the need to hold their horses on such tight reins and say to the horse with each step, “step”, “watch where you are putting your feet”, and then when the horse missteps, completely put the blame on the horse. I do have a question though. Is it accurate that a horse’s near vision is located at the top of their eyes, mid vision in the center, and far away vision in the bottom of their eyes which means that when they are looking at something far away, they have to raise their head and conversely, they lower their head to look at something very close?

Leesa,

Thanks very much for your comment. I’m not sure I understand your question. From what I’ve read, horses can see the horizon and the grass in front of them while they are grazing. But if something is in its periphery (at the edges of its vision), then objects DO appear less focused. Horses will move their heads to put whatever they need/want to see in better perspective.

I’m curious as to how a horse is capable of such accuracy in jumping obstacles of varying heights when I keep reading that horses cannot see down directly in front of them.

To clarify, horses eyes do not have lenses that adjust for depth perception the same way as humans. They raise and lower their heads to bring objects at different distances into focus. That is why you see them raise their heads to look at something in the distance. To restrict that is asking them to work blindly which understandably creates anxiety.