“Stressed” horses in the French study

Recent research on stress and learning in horses, conducted by a group of French scientists, has made a splash in horse media. The study, titled “Stress Affects Instrumental Learning Based on Positive or Negative Reinforcement in Interaction with Personality in Domestic Horses” involved work with 60 horses, using negative and positive reinforcement as well as an assessment of the horses’ personality. A few primers:

- Negative reinforcement is typically considered the “Pressure & Release” method of horse work in which you apply pressure and then release it when the horse responds with the correct behavior or movement.

- Positive reinforcement is rewarding a horse when it performs the correct behavior or movement, often with food.

- Personality, in case you were wondering, was assessed by each horse’s degree of fearfulness, gregariousness, reactivity to humans, level of locomotive activity, and tactile sensitivity.

- “Stress” here was induced by the horse not seeing its herd mates, and/or by experiencing a sudden event (like a barking dog or people talking loudly) and indicated by measurements of cortisol levels in saliva samples.

1st Finding: Stress impairs learning. That’s what this publication focused on here.

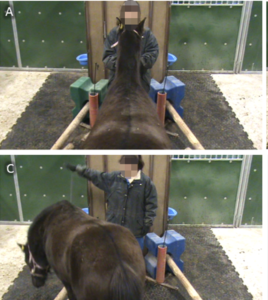

Did this image properly represent the “stress” study? Probably not.

But when you look more closely at the research, you discover how horses faired differently depending on which kind of reinforcement was used in the exercises.

2nd Finding: Positive reinforcement (giving a treat or otherwise rewarding the correct behavior) was less effective than negative reinforcement (applying pressure, then releasing when the correct behavior is achieved) when horses were being stressed. Read about BestHorsePractices’ thoughts on positive and negative reinforcement here.

“The results show that use of food reward as reinforcement may not be adequate in stressful conditions,” researchers wrote. Treat-giving was less effective with stressed horses.

The study also incorporated horse personality, measured by fearfulness and interest in novel objects, for example. Researchers found that horses’ personalities also impact their ability to learn. When positive reinforcement was used and stress was applied, the most fearful horses performed the task least effectively.

Our Take-Away: Taken in its whole and being mindful of the way the findings where interpreted and disseminated, the study offers a fabulous teaching moment in:

- how science works

- how reporters interpret the findings

- how horse owners react to the information.

It’s no surprise that other journalists have seized on different aspects of the study or that readers have grabbed headlines and drawn certain conclusions.

Is all stress bad? A moment of stress followed by…

Is stress really bad? What is stress?

From our perspective, it’s crucial to appreciate that one horse’s stressor may be another horse’s yawn-fest. One trainer’s idea of stressing a horse may also be vastly different than another trainer’s interpretation. Consider stress as the horse’s cup of coffee: Some love it. Some react badly to it. Some benefit from lots of it. Some have much less tolerance for it.

3rd Finding: In fact, horses experiencing negative reinforcement performed better when there were stressors in the mix. Many trainers believe that stress is an inevitable part of life (for humans and horses) and that learning to deal with stress is an essential component of training. Negative reinforcement is certainly a kind of stress. These trainers say that horses learn better when under some degree of stress and constant comfort is anathema, they say. Read more about the Cons of Comfort here.

The quickest learners in this study? Those classed as the most fearful (according to the personality tests) and who experienced negative reinforcement.

One more thing: Are stressors like the ones used here really stressful? Or, are they distractions that simply take the horses’ attention away from the task at hand? Are distractions stressful? Read more about attention here.

…a moment of relaxation

Like a lot of research, this study’s finest contribution may be in prompting more questions than it answered. When what we don’t know shines more brightly than what we do know, we here at BestHorsePractices get excited.

I’m wondering if those running the study may have had more valuable results had they classified the “personalities” with a more scientific approach. Right Brained reactive animals of any kind are already known to be… more reactive as well as less likely to eat anything when stressed. Left brained logical thinkers are far more curious about their environment and food in a way a reactive animal cannot (because it’s safety is of paramount concern). I’ll look again but I didn’t see where the cortisol levels were at prior, during and after the induced stressors. There is also the Introvert (non moving) and Extrovert (moving) behavioral personality aspects to consider.

Finally, simply getting a “Reaction” Positive or Negative out of an animal is a far cry from what many would consider Valuable “Learning”. What this study proved was that a Prey animal was capable of Reacting to the Stressors induced by Predators. This is hardly new news. What may be more helpful to the Industry as a whole is to see what the ultimate long-term effects of Predator Induced Stressors are on the Safe Reactions of the Prey animals in their study. For while you may be able to encourage a reaction out of an already reactive animal it is often an unsafe manner for both the animals and the humans in the equation. There is a long line at Slaughter houses Worldwide for Horses that have been made Overly Negatively Reactive by their human stress induced environment. Who doesn’t know of a horse that has been labeled for their unsafe behavior that was “learned” in an unfortunate aggressive interaction with humans? ‘Violence begets violence’ is age old. Unfortunately, it seems inevitable that the overly aggressive Profiteers in the industry will be thrilled with what this study’s flaws appear to prove.

Thanks for your comments, Marie. You have some valid suggestions, for sure. However, introducing what we consider Parelli horsenality language can be somewhat confusing to many readers. “Introvert” and “extrovert” are human-like terms that might initially be helpful when novices are introduced to horses. But ultimately, we find the terms misleading and ineffective when considering a non-human, non-verbal prey animal. Thanks again for your contribution.