Editor’s Note: What does learning a foreign language, Cisco Systems, and a threatening drill sergeant all have to do with horsemanship? Turns out quite a lot. As this article will explain, how we teach our horses to learn will have a huge impact on their attitude and how well they advance. Learn about Long-Term Potentiation and the keys and benefits of this optimal outcome from scientific and empirical standpoints.

Listen to Optimal Learning interview with Peters and Martin Black here.

By Maddy Butcher

A few years ago, Dr. Steve Peters, a neuropsychologist and director of the Memory Clinic at Utah’s Intermountain Healthcare,

was invited to talk to a group of leaders at Cisco Systems, the technology company.

The group wanted to know how best to teach Cisco’s complicated networking schemata to employees, in person and through teleconferencing and video platforms. Quickly and effectively, they needed to reach a broad audience with varied aptitudes for learning.

- How best do we do this?

- How do we keep them engaged and teach them so that they can move forward with their new knowledge?

To make his case, Peters got down to the nitty-gritty. He described what learning looks like on a cellular level. We’re not talking about rote memorization or short-term memory here, but rather, the absorption of knowledge for the long haul. It’s an outcome called Long Term Potentiation.

(We know “potential,” as the ability or capacity for growth. Potentiation refers to the growing strength of nerve impulses along previously used pathways.)

Listen to Optimal Learning interview with Peters and Martin Black here.

First, consider a typical, lazy learning moment:

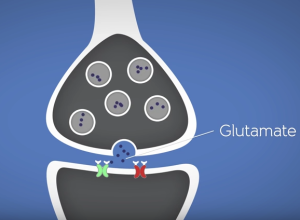

You’re listening, half-heartedly taking notes, and thinking in a distracted way about what you’re hearing. On a molecular level, the neurochemical glutamate is enabling the transfer of sodium from a presynaptic neuron to a postsynaptic neuron through so-called AMPA receptors. It’s a weak synapse and is not enough to cause Long Term Potentiation.

Now, consider a moment when you’re in the front row and at the edge of your seat. That engaging moment is followed by more reading and discussion with classmates. You feel good about your ability to expound on the topic (read more about dopamine’s effect on learning here).

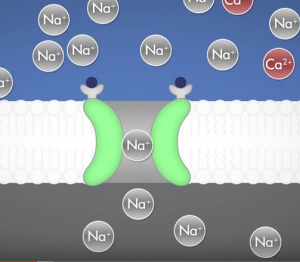

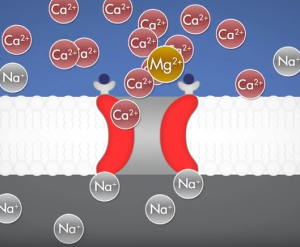

On a molecular level, an increased concentration of glutamate has let even more sodium through receptors of the post-synaptic cell. More sodium there causes a repulsion of a plug of magnesium that previously had been blocking another type of receptor, called the NMDA receptor.

With the magnesium bumped out, more sodium and now calcium molecules rush from one neuron to the other. Calcium, in turn, activates more intracellular cascades. In other words, there is greater activity and the connection strength of the presynaptic and

postsynaptic neurons increases.

That’s Long Term Potentiation. Watch this excellent video of LTP.

If getting smarter comes from the accumulation of sprinkles of connections, then LTP is when your brain shifts that sprinkle to a healthy pour of synaptic connections.

Lazy learning is a single-lane, ramshackle bridge, leading from one neuron to the next. After you pay the toll of increased focus and engagement, LTP is a wide, smooth thoroughfare of a bridge. Yahoo!

In the Cisco meeting room, people were intrigued. As horse owners we, too, should pay attention to this learning outcome.

Turns out LTP has a lot to do with how we present information, the teacher’s approach, and the students’ attitude. At this cellular level, the neuroscience for humans and horses is the same. (For all the Junior Scientists out there, for purposes of this discussion, LTP is occurring in the brain’s hippocampus, known as the region where memories are formed.)

How do we get our students (horses) to the point of LTP?

— Even if the work is tedious, it can and should be presented in a non-tedious manner. In other words, make it fun and get creative. Don’t repeat patterns over and over and over. Drilling will make your students (horses) frustrated, annoyed, and  resentful.

resentful.

— For maximum engagement, keep lessons short and energetic. Allow for recesses.

— For your student’s optimal learning, find his/her ideal psychological state between comfort and fear, between boredom and panic.

— Remember that threatening students with severe punishment can activate their fight or flight response. Neither horses nor humans can learn when they’re panicked.

— Incorporate on-the-job training and use immersion techniques. Foreign language students learn better when they are using that language and incorporating into other tasks. Horses learn about side-passing and turning on their fore and hind, when they are working with cows, moving through gates, or out on the trail.

Martin Black, co-author with Peters of Evidence-Based Horsemanship, sees a particular problem with riders who drill

repeatedly and believe their horses will learn best in the ‘warm and fuzzy’ zone of routine comfort. “Repetition can create  resentment. Horses can get frustrated, shut down, and take a defensive stance,” said Black. “If you build on that, they become more protective and more violent. I can’t tell you what it looks like. It’s a process.”

resentment. Horses can get frustrated, shut down, and take a defensive stance,” said Black. “If you build on that, they become more protective and more violent. I can’t tell you what it looks like. It’s a process.”

Read about the Cons of Comfort

As for riding without some occasional discomfort or excitement, said Black: “Students will say, ‘we don’t want to get them excited.’ My message is ‘yes, you do!’ We need to get them out of the comfort zone. And, that’s what the science is backing. Riders need to experiment.”

Often Black’s students confuse their horses’ alertness for panic and back away from a prime learning opportunity. “A curious horse has his head up. His eyes are alert. He’s taking it in. He’s not reacting in a self-preservation mode. He’s not

running or panicking. That’s where I’m trying to get people to go.”

While some riders have found this ideal learning state, many fall into two groups populating each edge of the territory: they are Nurturers and Warriors. Nurturers (mostly women) never get out of the comfort zone. Warriors (mostly men) are prone to bouncing off the flight or fight territory of horses’ sympathetic response. Read about the autonomic nervous system here.

A horse’s optimal state for LTP will look like this, according to Black and confirmed by Peters: “His head comes up. His ears come up. He’s taking in information. Maybe he’s starting to get tense, starting to get alert and is ready to do something.”

It’s the ideal moment for learning and an opportunity many riders unfortunately quash. “That’s when people start to get uncomfortable because they’re not sure what’s going to happen. But that’s precisely where people need to experiment if they are training a horse. Maybe the rider needs more experience and being successful without hitting the ground. But once you say, I’m going to be more of a trainer and less of a passenger, you’ll gravitate to this zone,” said Black.

“But if you can’t handle the one-rein stop, can’t stay on, get too scared, then your horse is not going to advance either. You, the rider, must have as many tools in your toolbox as your horse. It’s proportionate.”

Read about Dwell Time research

Read about the Wobble Board of Learning