Listen to Episode 7: Death Comes

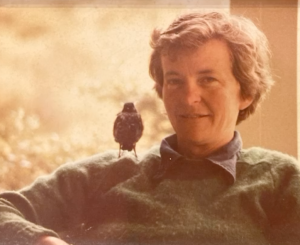

Sally King Butcher, aka, Mom

Music by Kevin MacLeod.

Since the last episode, I’ve driven about 8,000 miles, from my home in Colorado, to Kentucky, then Maine, then back to Kentucky, back to Maine, and finally, a return stretch to Colorado.

It has been an arduous month. And not just because it involved so much driving. As you will hear and read here, this episode is a departure from our usual rollout of knowledge and education-based interviews and discussions. You might think it’s self-indulgent or off-topic. We think it isn’t. But I trust you will let me know.

It’s about death and how we live with it.

As they say, death is part of life and since we all will experience it and since we live through deaths of loved ones, two-legged and four-legged, I thought it might be worthwhile. It’s certainly worthwhile to me because the process has meant writing about it, which means thinking about it, turning it around and around, like a prism in my hand, pondering my actions and reactions, thinking about ways to move forward, doing some research, and considering how other people – not just friends and family, but professionals, including therapists, think about this milestone.

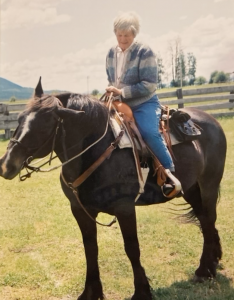

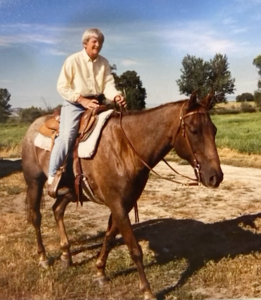

Sally Butcher leads her granddaughter on a short ride.

I traveled east to direct the Best Horse Practices Summit, in Lexington, Kentucky, but also to see my mom. Over the summer, it became clear that she would likely not live out the year. My family, best we could, made plans to support her and my dad, her sole caregiver, and, of course, to travel to Maine.

I think like many of you, my adult years have involved a lot of reflection on my childhood and how my parents shaped who I became as an adult. It has not been an easy road. It’s been a road marked by transitions, most recently as someone who feels quite a bit of compassion towards my parents, who, of course, were once young adults, doing the best they could to raise upstanding kids.

My mom and her mom, my grandmother, are two big reasons why I started riding and caring for horses as a girl. They grew up riding and continued to ride in their adult years.

Owning a horse was not an option, I was told, but when an opportunity came to take care of an acquaintance’s horse up the road, my Mom approved. Starting at age 12, twice a day, I would walk, run, ride my bike, or get a ride up to Skolfield’s Barn, a mile and a half from our house, to care for Honey, a big, naughty Welsh pony. I say naughty with the utmost affection. Honey figured me out immediately: I was naïve and novice, but also athletic and adventurous.

Sally and friend

We would head out alone on the trails and Honey, ever the one to keep me honest and alert, would shy at her first opportunity. This quick, sideways jump would happen just as I was relaxing into the ride. She felt my body shift and took that opportunity- every ride! – to educate me in her ways. For dozens of rides, and I mean dozens, she would come out from under me, trot five strides and look back as if to say, ‘gotcha again, girl. When are you gonna learn?’ I did, but boy, was I a slow learner.

It was the beginning of a horse-rider love that lasted a decade, hundreds of rides, and wouldn’t have happened without my mom’s support.

Mom was not a helicoptering parent, nor was she particularly warm and fuzzy.

She had little tolerance for the gushing love affairs that captivate the internet nowadays, in which connection to the horse is kind of lopsided and sappy. I think she’d say, “Okay, that’s all lovely, but what exactly are you getting done? How is the horse benefitting?”

She had little tolerance for the gushing love affairs that captivate the internet nowadays, in which connection to the horse is kind of lopsided and sappy. I think she’d say, “Okay, that’s all lovely, but what exactly are you getting done? How is the horse benefitting?”

This is not to say she didn’t dote on animals, dogs especially. But she always was putting them to work, too. Over her lifetime, she had hunting dogs, agility dogs, and therapy dogs. A productive life was a happy life, she said.

Yep. She loved animals, but, boy, was she one to anthropomorphize. I would chide her for the way she liked to project her human thoughts and ideas onto animals. Her life was full of dualities like this. Some might see it as being conflicted or hypocritical, I’ve made peace with it; that’s just Mom being Mom.

She balanced how she should be with what felt good. That she was of two minds was just part of how she got through her days.

My dad wrote a poem about her that talked about this. It’s called Life on the Road (For Sally) and goes like this:

My dad wrote a poem about her that talked about this. It’s called Life on the Road (For Sally) and goes like this:

A roadside restaurant in Forsyth is not

A smart stop for one who thinks about

triglycerides.

The breakfast special is sure to be

Two eggs (any style) with Ham,

Home Fries and see-through Coffee.

She could drive on to Billings,

but thinks maybe they’ll have a small plate

of Cottage Cheese with Fruit Cocktail.

A vase of daisies on the table

holds promise, the coffee is good, strong.

and she examines the menu with care,

including the “Healthy Heart” section.

Sun on the flowers, flicker of a distant light:

something changes before she decides.

“I’d like the Eggs Benedict, Strawberries with Whipped Cream, an order of Bacon.Yes,

and Whole Wheat Toast – unbuttered.”

Barry

In some ways, Mom was more connected, more bonded with animals than the humans in her life. I believe animals offered her a reliable, loving, non-judgmental space beginning early in her childhood, which was challenging to be sure. Her dad was in the military and the family moved some 12 times in 12 years. He came home from the war, this would be the second World War, and died shortly thereafter. She was 12.

I got to Maine on October 8th.

I’d not seen my mom since March and she had declined significantly, physically as well as cognitively, since then. Pretty much confined to a hospital bed in the downstairs bedroom, she nonetheless recognized me right away. There was a fleeting sparkle in her eye. We talked a little bit while I tried to hold off tears. I had been preparing myself for this time for weeks, talking with myself, talking with friends, my therapist, and my brother about it. I compare it to being properly prepared for a horse’s buck or bolt. I was trying to be relaxed. Calm and present but ready for a rough go. Do you know what I mean?

Well, we know that preparing for a buck or a bolt can morph into bracing for that buck or bolt or becoming completely preoccupied or paralyzed with the expectation of a buck or a bolt.

In hindsight, all my supposed mindful preparation went right out the window when the intensity and pain of the moment actually arrived. It was a lesson in being present and letting myself “feel the feels” as my partner, Shane, would say. I couldn’t stay. I couldn’t stick the buck. I left the room, said goodbye to my dad, and went to get some rest at a friend’s place that night.

In hindsight, all my supposed mindful preparation went right out the window when the intensity and pain of the moment actually arrived. It was a lesson in being present and letting myself “feel the feels” as my partner, Shane, would say. I couldn’t stay. I couldn’t stick the buck. I left the room, said goodbye to my dad, and went to get some rest at a friend’s place that night.

Feeling like I lost my nerves and bailing out on that first, difficult visit was a lesson on many levels. But most importantly, for me and my hindsight, it has been about redefining resilience and leaning into vulnerability.

Moving forward, I’m saying to myself, resilience is not going to mean toughing it out or bracing for impact.

Vulnerability, discouraged on all counts in my family when I was a girl and through adulthood by my own conditioning, is going to be newly allowable.

I would feel the feels, fall apart if I needed to, and still be there to support Mom and my brother and my dad. I leaned hard on my closest people to navigate this course and, as ever, I was not perfect. I am not perfect. But I am showing up and trying.

In the coming days, hospice increased their visitations to every day. Mom declined precipitously, from feeding herself to having me feed her, to not wanting or being able to eat at all. She died a week after I arrived, with her husband and her two children by her side. I should add that our three dogs had been sitting vigil for days. They read the room and felt the air. They knew. Barnie, Tina, and Monty were there, too, when she died. She would have loved that. Or, maybe I should say, she loved that.

In the coming days, hospice increased their visitations to every day. Mom declined precipitously, from feeding herself to having me feed her, to not wanting or being able to eat at all. She died a week after I arrived, with her husband and her two children by her side. I should add that our three dogs had been sitting vigil for days. They read the room and felt the air. They knew. Barnie, Tina, and Monty were there, too, when she died. She would have loved that. Or, maybe I should say, she loved that.

The author, Francis Weller, who wrote The Wild Edge of Sorrow, says that in today’s world we numb ourselves. We urge ourselves to forget instead of grieving properly.

He writes: “In this culture we display a compulsive avoidance of difficult matters and an obsession with distraction. Because we cannot acknowledge our grief, we’re forced to stay on the surface of life.”

Following Mom’s death, that’s what I did. The funeral home came to take her body. The service, a celebration of life, was arranged for later in the month. I wrote the obituary for the papers and left to direct the Best Horse Practices Summit with the “this-is-what-she-would-have-wanted” idea firmly in my head.

I was incredibly fortunate to have a supportive staff at this conference. Thanks to them, I was able to perform my director duties and let them pick up tasks I simply could not manage to do without breaking down. Public speaking – wwaayy different than talking into this microphone with two totally disinterested dogs sleeping nearby – is hard for me, even when I haven’t just lost my mom.

I was incredibly fortunate to have a supportive staff at this conference. Thanks to them, I was able to perform my director duties and let them pick up tasks I simply could not manage to do without breaking down. Public speaking – wwaayy different than talking into this microphone with two totally disinterested dogs sleeping nearby – is hard for me, even when I haven’t just lost my mom.

Board president Josh McElroy read my opening remarks, which were about losing my horse, Shea, this summer. I know, I know. What the heck I was thinking to write about such a difficult time? For the record, my point in talking about Shea was to highlight the conference’s offerings, gifts of knowledge to help dispel the questions we ask ourselves when things don’t go well. So anyway.

After the conference, I drove the thousand miles back to Maine. There, I wrote and practiced what I’d say at her service. I connected with my cousin, Martha – she’s one of my favorite human beings and a doctor in North Carolina. She’d be coming up for the service and wanted to read a Wendell Berry poem. We added that to our little Celebration of Life program.

To prepare for this other kind of public speaking, one I had never done before, I reminded myself that I would be surrounded, really surrounded, by loved ones and people who cared deeply for my mom. The audience would be, as someone once told me about public storytelling, a big communal hug.

And so it was.

Shane and I left Maine the next day for the long drive west.

En route, and less than 24 hours after my Mom’s service, I got a call from my friend, Rebecca, back in Colorado.

En route, and less than 24 hours after my Mom’s service, I got a call from my friend, Rebecca, back in Colorado.

Just a little background here: I had left my three horses at Rebecca’s 40-acre pasture, with her six horses. I had hauled my guys over two days before leaving, to make sure they had time to adjust, learn the lay of the land. and get to know their pasture mates. And they did. She reported regularly that they were happy and getting some winter fat on them.

As I bet every one of you knows, seeing the number of the person who is taking care your horses pop up unexpectedly on your phone can make your heart sink, or go to your throat, or can make your gut drop immediately.

And so it was.

My beloved horse, Barry, had died overnight. Tragically. In a fluke accident that could not, I don’t think, have been prevented. I sure wish I had the tenacity and wherewithall to explain it here. But I cannot. I guess you will have to take my words as so.

I was and still am crushed.

Barry was a rescue who took 20 minutes to catch when I first got him. He was Wary Barry. He was Scary Barry. We were on a big journey together that involved undoing his reactions to what he saw as human practices that would surely hurt him – things like bridling and saddling, things like riding faster than a walk.

Over three years, we had come so so far. The licking and chewing and yawning during our times together is something I will not soon forget. Over time, he trusted me with the world. I rode hundreds of miles with him in the mountains, off the sides of mountains. He packed hundreds of pounds of salt for me as a pack horse. He moved cows.

On our last ride, I ponied two horses off him. That’s something that just a year ago would have freaked him out. He was nervous on that day, but hung in there like the horse I knew he had become. Stretching his comfort zones as I was stretching mine.

Barry valued relationships not just with fellow horses, but across species. He would look for me and pay attention to what I was doing and how I was doing. I’m smiling at the games he would play with my dog, Monty. They would taunt each other from across the fence, playing this hilarious, horse-dog game of I’m-gonna-move-this-way, what-are-you-gonna-do? As I helped him become more relaxed and engaged, he became a beautiful presence in our little multi-species family. Whatever I might have provided to Barry, in the way of helping him get to a better place, he gave back three-fold.

Barry valued relationships not just with fellow horses, but across species. He would look for me and pay attention to what I was doing and how I was doing. I’m smiling at the games he would play with my dog, Monty. They would taunt each other from across the fence, playing this hilarious, horse-dog game of I’m-gonna-move-this-way, what-are-you-gonna-do? As I helped him become more relaxed and engaged, he became a beautiful presence in our little multi-species family. Whatever I might have provided to Barry, in the way of helping him get to a better place, he gave back three-fold.

I’d like to say I have profound relationships with all my horses. But you know. With some horses we connect more than others. That’s the way it was with Barry and me. Together, we were works in progress.

His death was traumatic. My grief around his death has been traumatic.

It has been especially difficult to juxtapose Barry’s death and my mom’s death. One, an animal I took care of for about four years, and then the other, my very own mother, who I knew for almost 60 years. Why was I feeling so much more upset over Barry’s death? Was something wrong with me?

Well, for starters, it was a shock. But I also think Barry’s death was the straw that broke my back. When my mom died, there was a lot of relief mixed with the grief. Her quality of life, having dementia and crippling arthritis and scoliosis and cancer, had not been good for a long time. She had had a really nice life and died peacefully. Like Shea, Mom’s best years were certainly behind her. Barry’s, on the other hand, lay ahead of him.

His death left me feeling numb and literally at a loss for how to carry on. I think so many of us think about carrying on and getting over it. It’s our culture to numb ourselves, to distract ourselves, rather than sitting with the grief and feeling the feels. It’s also our culture to deal with it alone, rather than sharing what we see as a burden for others.

Isn’t it funny that if we had a friend who said, ‘hey, I’m really hurting and need to share something with you and lean on you for a moment.’ That then we would welcome it, right? But how often do we think to do that ourselves, to seek a shoulder to cry on and reach out for support?

My son sent me The Geography of Sorrow, an interview with Francis Weller, who I mentioned earlier. Weller says that nowadays, “we’re asked — and sometimes forced — to carry grief as a solitary burden. And the psyche knows we are not capable of handling grief in isolation. So it holds back from going into that territory until the conditions are right — which they rarely are. The message is “Get over it. Get back to work.” Clients come to me with a depression that is more of an oppression: a result of so many years of sorrow that have not been touched with kindness or compassion or community. You’re left with an untenable situation: to try to walk alone with this sack of grief on your back without knowing where to take it… Our hyperpositive tendencies want us to do a spiritual bypass around the mess of it all, but it’s there in that mess that we are most human.

“We simply can’t avoid the losses, wounds, and failures that come into our lives. What we can do is bring compassion to what arrives at our door and meet it with kindness and affection. We can become a good host.”

That’s what I was thinking when I was mentioning my new outlook around resilience and vulnerability a few minutes ago.

Weller talks about balancing grief with gratitude.

He says, “There’s no way to be spared sorrow. Everything I love, I will lose. That’s the harsh truth. You either have to shut down your heart — and miss the love that is around you — or wrestle with that truth and come out the other end.

“The work of the mature person is to carry grief in one hand and gratitude in the other and to be stretched large by them. How much sorrow can I hold? That’s how much gratitude I can give. If I carry only grief, I’ll bend toward cynicism and despair. If I have only gratitude, I’ll become saccharine and won’t develop much compassion for other people’s suffering. Grief keeps the heart fluid and soft, which helps make compassion possible.”

He says that if we don’t work to acknowledge our grief, we’re forced to stay on the surface of life. He quotes poet Kahlil Gibran who said, “The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain.”

It goes against my nature, my conditioning as they say in today’s vernacular, to talk about this past month. But I have been trying to do so. Sharing my experiences is something I hope will help others. And, yes, sure, I hope it will help me, too.

Weller says you cannot think your way through grief. This is hard for me to hear. As an amateur intellectual, I like to think we can think our way through everything!

But it’s true. Grief has been a bodily experience. My chest has been tight. My stomach has been upset.

I’m trying to listen to my body and give it what it needs. Right now, that seems to be crying and exercising in equal measure. I am trying to embrace the image of carrying grief in one hand and gratitude in the other. It’s not fun at the moment, but I feel like some day, it will be.

Listen to Episode 7: Death Comes

Music by Kevin MacLeod.

Thank you for sharing this with us Maddy. Sending all the love and all the feels.

I so understood what you wrote, wholeheartedly. Lost both my parents (in their 90’s) in recent years and lost my Azteca mare, only 11, just a few months ago. Part of me is empty, the rest of me knows life is beautiful. God bless…

Carol in Colorado

Thanks Maddy. Your apple sure didn’t fall far from the tree. God Bless you. Vince

Condolences to you. My life has been littered with loss for the past decade, human & animal. I recently told my BF that sometimes I feel like the angel of death. In her wonderfully practical way she said no, you just have a larger than average number of loved ones in your life so your odds of experiencing death are higher! I had to laugh. For me these losses, along with the expected grief, opened floodgates of other “stuff”. Mostly fear. Fear of more loss, fear of pain. of abandonment, fear of not being good enough. It’s a challenge. I really enjoy Cayuse and Best Horse Practices. Thank you for what you do.

Dear Maddy,

When I saw you and heard you speak at your Mom’s Celebration of Life, I was so proud of you and overwhelmed by your strength, dignity, and bravery. Under such sad circumstances, as you shared some beautiful stories of your Mom, I was genuinely overwhelmed. You spoke from your heart and every fiber of your body.

Once again, opening up your heart to us and sharing your love and your losses this summer brought tears to my eyes. It also made me so proud to witness firsthand the strength and character that your Mom instilled in you. Your Mom’s amazing work with her two and four-legged families will be carried on by you. Tough shoes for you to fill, as her legacy to you is so rich yet we are all better for your sharing her with us.

Love and gratitude to you and many thanks for allowing us to be part of your life.

Maddy, facing these turmoils does sadden us terribly, but also makes us recognize joys more fully. Thank goodness for your insights and your experiences, both with your beloved horse and your Mom , who could be a conundrum! Blessings and healing! Thanks for sharing your feelings so bravely!!

Maddy we are saddened to hear of your mom’s passing. We will always remember the family time she arranged at the White Tail. She had such joy of

You all being together. She watched you all from the front porch with happiness. She was a very nice lady with a calming way about her. Beautiful memories. May your memories of love and fun times bring you peace.

Grief. . . . Yes, my latest. Over my rescued puppy whom my husband detested. It was the puppy’s loud, demanding bark insisting I pay immediate attention. We’d lost our gentle giant Akita after nine wonderful years. He too, was a rescue. I was torn . . . get rid of this noisy darn puppy. Give him back to the Rescue woman. And I did as I was told. I gave my puppy boy back and began to grieve. I would not look at my husband, or talk to him, or explain why I was crying and yelling, and refusing to communicate. I was hiding.

Finally he gave up . . . and I begged the Rescue to allow me to have my puppy back. After hearing the grief in my voice, she forgave me and arranged for me to pick up my little boy. I still had a hard time looking at my husband or speaking to or with him. That has waned now, but it took a bit of time for my emotions to settle back. And . . . I still wonder at the depth of my grief over this young animal.

Thank you from the bottom of my heart. You have spoken the truth in all you have said. Raw feelings from your heart that I appreciate. I would love for you to take a moment and Google Search and listen to “12 Truths I learned from Life and Writing, by Anne Lamott. Number 12 will knock your socks off. She is amazing, like you.

Love and hugs to you through this difficult time in your life.

Thank you from the bottom of my heart. You have spoken the truth in all you have said. Raw feelings from your heart that I appreciate. I would love for you to take a moment and Google Search and listen to “12 Truths I learned from Life and Writing, by Anne Lamott”. Number 12 will knock your socks off! She is amazing, like you.

Love and hugs to you through this difficult time in your life.

Maddie, My deepest condolences on your losses…Thank you for so eloquently expressing how our culture inhibits us from experiencing our grief. It is a painful journey, but the intensity of emotion is a reflection of how much we love. Sounds like your mom was a beautiful person, you were lucky to be her daughter. And Barry was so fortunate to have you as his human, sounds like you learned a lot from each other💞

Sending love to you from the PNW…