What is a smile or a handshake?

What is a smile or a handshake?

The answer is like a Matryoshka doll with another doll inside it and then another doll inside that one.

Sure, they’re gestures of welcome. But neurologically speaking, they are the manifestations of a bundle of voluntary and involuntary movements. Inside that doll, they are the result of action along neural pathways, involving the firing of millions of synapses. And inside of that doll, the handshake or smile is ultimately influenced by the scores of neurochemicals, traveling and existing in relative homeostasis in our brains and throughout our bodies.

Neurochemicals like dopamine and serotonin are prominent in most mammals and their functions are multifold. They play a role in almost everything we do.

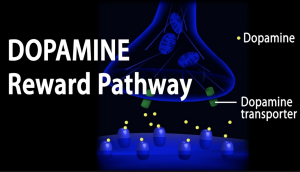

For instance, we know dopamine as the chemical of reward, but it’s also vital to movement (Parkinson patients, for instance, lose the ability to produce dopamine. Therefore, they may struggle to perform voluntary movements without taking synthetic dopamine.). Read more on dopamine here.

Serotonin may be the ‘happy chemical’ but it is also vital to digestion. Read more on serotonin here.

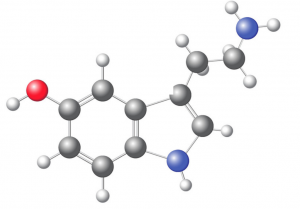

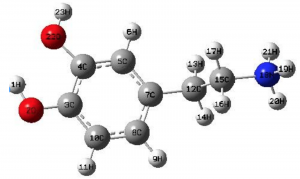

Molecular structure of Serotonin

Behavior is the big wooden doll. At BestHorsePractices, we like to open up the doll and exame the little dolls within. What’s inside a given behavior? Let’s talk about causes, psychological and physiological impact, treatment, and consequences.

Considering cribbing:

Cribbing, that troublesome act of using incisors on a surface to flex neck muscles, retract the larynx, and allow air into the esophagus, is a stereotypy, a ‘repeated behavior serving no obvious purpose,’ says Merriam Webster. Stereotypies are an adaptation to stress and have been shown to impair learning. Another study notes that if a cribbing horse is allowed to crib, then it can learn just as well as a non-cribber.

Cribbing is also the bane of hand-wringing horse owners and a steady source of income for the industry, which offers myriad tools for “combatting” the behavior.

Dopamine

It’s important to think of cribbing from the horse’s perspective: I’m simply adapting to environmental stressors which limit my ability to take care of myself and cause me to seek solutions outside of my natural behaviors.

Here, with the help of Dr. Sheryl King and Dr. Steve Peters, we breakdown the causes and science behind cribbing, evaluate treatments, and debunk myths:

As part of their healthy behavioral repertoire, horses need to chew, move, interact with other horses, and have access to forage almost constantly. Confined and isolated horses become stressed horses (even if they don’t outwardly appear stressed). Their inability to move negatively impacts their neurochemical and physiological balance.

When we stall them, limit chewing opportunities, and compromise their diet with concentrated feed (grain) instead of forage, we create stress. Empty stomachs are more prone to ulcers. This study suggests grain is cribogenic.

When compared to unstalled horses in group environments, stalled and isolated horses often exhibit elevated levels of cortisol (known as the stress hormone) and decreased levels of serotonin. Lower serotonin levels have been shown to be associated with the introduction of compulsive behaviors.

When compared to unstalled horses in group environments, stalled and isolated horses often exhibit elevated levels of cortisol (known as the stress hormone) and decreased levels of serotonin. Lower serotonin levels have been shown to be associated with the introduction of compulsive behaviors.

In the case of cribbing, we believe that the horse tries to create saliva as a bromine – like Tums for us – and discovers that biting onto something helps. (Unlike humans and other species, horses do not salivate without direct oral stimulation.)

Meanwhile, the brain responds to stress by producing beta-endorphins (natural analgesic neurochemicals) that boost the sensitization of dopamine receptors. The cribbing behavior becomes a highly self-reinforcing system, a cycle which peaks with the release of dopamine.

Studies show that horses lower their cortisol levels and heart rate by cribbing.

Horsespeak: I’ve adapted!

Through poor management, horses become stressed. Stress creates a neurological domino effect that results in a dopaminergic super-pathway (small doll) manifested in cribbing (big doll).

Through poor management, horses become stressed. Stress creates a neurological domino effect that results in a dopaminergic super-pathway (small doll) manifested in cribbing (big doll).

You now have a cribbing horse. A stressed horse that has found a stereotypy that makes it feel better. Certainly, the management and resulting stereotypy impact its neurochemistry and outward behavior, researchers have also found that stereotypies are detrimental to learning.

Nature or Nuture?

Studies show that thoroughbreds and warm bloods are at greater risk for cribbing. But is this related to their genetic makeup?

Are these breeds more prone to stress responses? Are they simply more likely to end up in a stall?

Stallions are more susceptible than mares. Genetics or the way we manage stallions?

A better scenario

Some research indicates that horses may be more susceptible to stereotypical behavior due to a genetically determined increased number of dopamine neurons and therefore a lower threshold for stimulation. This study considered genetics and cribbing.

Treatment Options, or, What to do with a cribber?

Contrary to popular opinion, chronic cribbers are not more susceptible to digestive problems. Aside from marking up fences and stalls with their incisors and wearing down their incisors prematurely, nothing terrible will come from cribbing.

Pharmaceutical treatments

Drug treatments may be given to block dopamine or opioid receptors and reduce the pleasurable effect of these neurotransmitters. These are known as dopamine or opioid antagonists or inhibitors.

Naloxone, for instance, has been shown to reduce cribbing and is the same agent used in drug rehabilitation clinics for heroin addicts.

Fluphenazine is a long-acting dopamine antagonist (and an anti-psychotic drug for humans) has been used to combat cribbing, with limited results.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI’s, better known as antidepressants) have also been used to reduce cribbing.

Cribbing straps don’t work

Dextromethorphan (a common cough suppressant for people) is an opioid antagonist.

But why subject a horse to the myriad side effects of drugs?

Why subject your wallet to repeated gouging?

If the axiom “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” were ever fitting, it would be so for cribbing.

As with any addictive behavior, the key is to avoid putting horses in stressful environments that cause the horse to seek an adaptation in the first place. Once your horse starts to crib, it will likely never stop, regardless of your effortful and expensive attempts to mitigate it.

What can you do for cribbers?

- Turn them out to a paddock or pasture

- Allow them to be with other horses

- Offer them hay, grass, and no grain

Cribbing straps? They don’t work.

Research shows that aversive equipment or training is counterproductive and may only add to the horse’s stress. Worse, they may cause the horse to develop another stereotypy that has not (yet) been restricted.

Stereotypies are not learned behaviors. Therefore, the horse cannot and should not be punished for cribbing. Training it to unlearn cribbing won’t work either.

Adds Dr. King: What’s even more concerning is cribbing surgery where they remove the muscle in the throat latch area that the horse uses to open his larynx to gulp air. This may physically prevent the horse from cribbing, but it does nothing to address the conditions that led to the stereotypy in the first place. I would not be surprised to find that there are all kinds of psychological and possibly physical repercussions to this surgery

Additional note: Cribbing is not contagious. Unfortunately, this myth may result in exacerbating the cribbing horse’s stress, since an owner might further isolate the horse from others.

Turn ’em out if you can!