Randy Rieman fulfilled his childhood dream of becoming a horseman when, in his early 20’s he left the midwest and traveled to Montana. With a keen willingness to work hard and an enthusiasm for learning, he connected with many fine horseman, including Bill and Tom Dorrance in California. For the past 30 years, he has honed his craft in California, New Mexico, Hawaii, and, of course, Montana, which he now calls home. Along the way, he’s also risen to the top as a rawhide braider and a cowboy poetry reciter. He travels nationally and internationally to share what he’s learned.

Randy Rieman fulfilled his childhood dream of becoming a horseman when, in his early 20’s he left the midwest and traveled to Montana. With a keen willingness to work hard and an enthusiasm for learning, he connected with many fine horseman, including Bill and Tom Dorrance in California. For the past 30 years, he has honed his craft in California, New Mexico, Hawaii, and, of course, Montana, which he now calls home. Along the way, he’s also risen to the top as a rawhide braider and a cowboy poetry reciter. He travels nationally and internationally to share what he’s learned.

Read about his Dorrance memories.

Watch his BHPS talk with Bryan Neubert.

Here, Randy Rieman sits down with us to talk about gradients of feel and knowledge

Bill Dorrance always told the story about the old cowboy and the young cowboy:

The young cowboy says to the old cowboy, “You sure have good judgment. How did you get such good judgment?”

And the old cowboy says, “Lots of experience.”

The young cowboy asks, “Well, how do I get the experience?”

The young cowboy asks, “Well, how do I get the experience?”

The old cowboy says, “Bad judgment.”

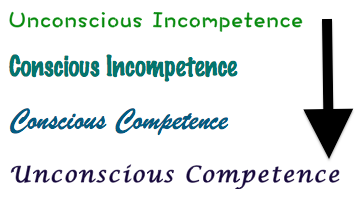

You see, we start out at Unconscious Incompetence: we don’t know what we don’t know.

We move toward Conscious Incompetence: we know what we don’t know. And then we move toward making information into knowledge by experience, leading to wisdom. We then have Conscious Competence: I know what I can do and I know what I can’t do. I know what I’m missing.

And then we get to intuitive intelligence or the non-verbal intelligence. That’s really Unconscious Competence: I don’t need to ask myself why I did that. I just know it was right.

That’s really the process we all go through. There are some people who are extremely gifted with something. It might be visual art or music or it might be the ability to recognize that critical inch in what they are doing. I think there are certain people who know what to do without being told.

Bill talked about his brother Fred being the best observer he’d ever seen. He could see someone doing something and understand why it worked by watching. He didn’t have to be told. He could see it. And Bill said the remarkable part of Fred was that he could add it to what he already knew, on the spot. He was “extremely mentally flexible,” Bill said. He could see the critical part and just incorporate it. But Bill said his brother could not help you do anything because he could not verbalize it.

[Fred Dorrance drowned at age 33, in a freak duck hunting incident. He had shot a duck and couldn’t swim, so he striped down and piled his clothes and his shotgun on the saddle and rode his horse bareback into the pond to get the duck. They both got tangled up in the underwater weeds and drowned, said Rieman]

On teaching horsemanship –

It’s interesting to me – this clinic thing and exchange of information — I like mystery but I don’t like mysticism. A lot of people try to create mysticism by being ambiguous and by not answering direct questions. That keeps them at an elevated status among the practitioners.

The reason I try hard to verbalize is because I want students to know: this is not mysticism. You can earn this. You can work your tail off and you’re going to discover this stuff, too. No one was born knowing it all. Although some people are more gifted tactile-ly, they have a more sensitive sense of feel. Some people have a real gift for observation, too. They really see what they’re looking at.

Tom Dorrance’s old mantra was Observe, Remember, and Compare. You’ve got to see what you’re looking at so that you can spot the differences. But you have to feel that, too. That’s the thing – many of us don’t get the opportunity to ride many horses. I was really fortunate to ride lots of horses. It took a long time to feel some of that stuff. You don’t get that chance when you ride one horse a few times a week over 20 years. You get that chance when you’re riding 10 or 15 a day for a decade.

It’s really hard to convince people they are really different. What happens most of the time is people will find a horse that’s a lot like the horse they always  rode. It’s familiar. But it’s nice to have the ability to adjust. It involves what Tom and Bill talked about, “mental flexibility.”

rode. It’s familiar. But it’s nice to have the ability to adjust. It involves what Tom and Bill talked about, “mental flexibility.”

Tom always said the best horses end up in the dog food can because they’re too sensitive. But they would be the best ones if you could meet that sensitivity. Most of us have to dull them down to our level. There’s some validity there because we’ve got to stay safe. But this is why I hate the term desensitize. I don’t want them to be desensitized. I want their emotions to be under control, but I want them to remain sensitive to the right things.

Tom would said: “I want to leave all that in there. I want to educate him so that he knows I’m not a threat and what we’re doing is not a threat.” And then I’ve got all the sensitivity, so I don’t have to pedal him. I don’t have to pull on him. I can make a suggestion and I’ll get a response.

You’re not desensitizing them, you’re educating them.

That whole idea is just different from ‘You’re the Boss.’ You do have to be the leader. But a lot of times you’ve got to give that horse some latitude and that can be frightening. When a horse is real lively and sensitive, that’s intimidating to someone without a lot of experience. It seems to be a little more than they can handle. So, the safe thing is to dull all that down. And that’s why I think this desensitizing thing has gotten so popular.

A lot of horses can end up being punished for moving. They’re reluctant to really free up and go somewhere because they’ve offered too much and gotten shut down. That’s when you need that ability to go with the horse when they need to move. If you can go with that and learn to direct it, you can maintain that lively feel.

A lot of horses can end up being punished for moving. They’re reluctant to really free up and go somewhere because they’ve offered too much and gotten shut down. That’s when you need that ability to go with the horse when they need to move. If you can go with that and learn to direct it, you can maintain that lively feel.

I see a lot of dull horses. They’re dull because they’ve been prodded on after they answered the request for motion. And so, what happens is those cues lose their effectiveness. If you call someone on the telephone, as soon as they answer, the phone stops ringing. If you are asking with your legs to initiate motion, as soon as the motion is initiated, you have to stop asking for it. If you keep asking, you’re going to lose that meaning and effectiveness. The horse gets duller and duller to your request.

Coming next:

The really good hands aren’t rewarding the result, they’re rewarding the intention.

Great article! Love the explanation about desensitizing and education….makes so much sense.