Editor’s Note: Amy Skinner is a regular guest columnist and has been a horse gal since age six. She runs Essence Horsemanship, rides and teaches English and Western at Jim Thomas’ Bar T Ranch. Skinner has studied at the Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art in Spain, with Buck Brannaman, Leslie Desmond, Brent Graef, and many others. She

heads to Maine next month to teach lessons.

Recently, Skinner attended the Healthy Horse Seminar which featured Dr. Steve Peters. She writes about applying what she learned to her work.

She writes:

It’s a very exciting time in the horse world right now. There’s more information available to the layman than ever. We have a better understanding of the horse physically and mentally, and with Evidence-Based Horsemanship, it seems like we literally have an operations manual with a scientific approach to the horse’s brain.

As a trainer, all this new science-y information swirled around in my head and I looked for ways to apply it. When Dr. Steve Peters talked about keeping horses interest peaked without panic setting in, I thought about how I often went about trying to introduce a horse to something new and scary. I set out to experiment a little, to get out of my set ideas of how horses “should” be trained and just be a scientist for a little bit.

Peters will present at the Best Horse Practices Summit.

The Bar T Ranch is home to five cows. They live in a field behind the arena. Sometimes, I think they get a kick out of seeing what sort of trouble they can stir up; they might lie down by the far end of the arena and stand up just as I ride a young horse near them. To the colt, I imagine this looks like a monster just popped up from underground. Several horses in training have some aversion to the monster end of the arena.

The Bar T Ranch is home to five cows. They live in a field behind the arena. Sometimes, I think they get a kick out of seeing what sort of trouble they can stir up; they might lie down by the far end of the arena and stand up just as I ride a young horse near them. To the colt, I imagine this looks like a monster just popped up from underground. Several horses in training have some aversion to the monster end of the arena.

One horse is particularly scared of the cows. I’ve ridden him around them and worked the cows off him. He’d settle down for the moment, but his deep suspicion lingered and every new day in the arena he’d spot the cows and start snorting and bracing his neck and head like a submarine periscope.

Dr. Peters explained how a horse can vacillate between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. In my new mindset of experimentation, I took the colt to the far end of the arena with a bucket of grain and set it right by the fence. The cows, curious and greedy, came running. At first, the little colt eyed the cows with concern, unable to eat his grain. But after a few minutes he started munching, even with the cows poking their muzzles through the gate. He lifted his head up out of his bucket and for the first time touched the cows with his own muzzle, then went back to eating.

After he finished the grain, I worked him on the ground and allowed him to stretch his neck down and sneeze. He let go of his back and walked balanced circles. I then rode him past the cows for the next hour. He was buttery in my hands and stretchy through his back. From Dr. Peters lectures, I know that the colt had successfully down-regulated, in other words, with that healthy exposure, the horse was now responding less to the stimulus. He was no longer concerned about the cows and more interested in paying attention to me and having his body be aligned.

Read more about the comfort zone here.

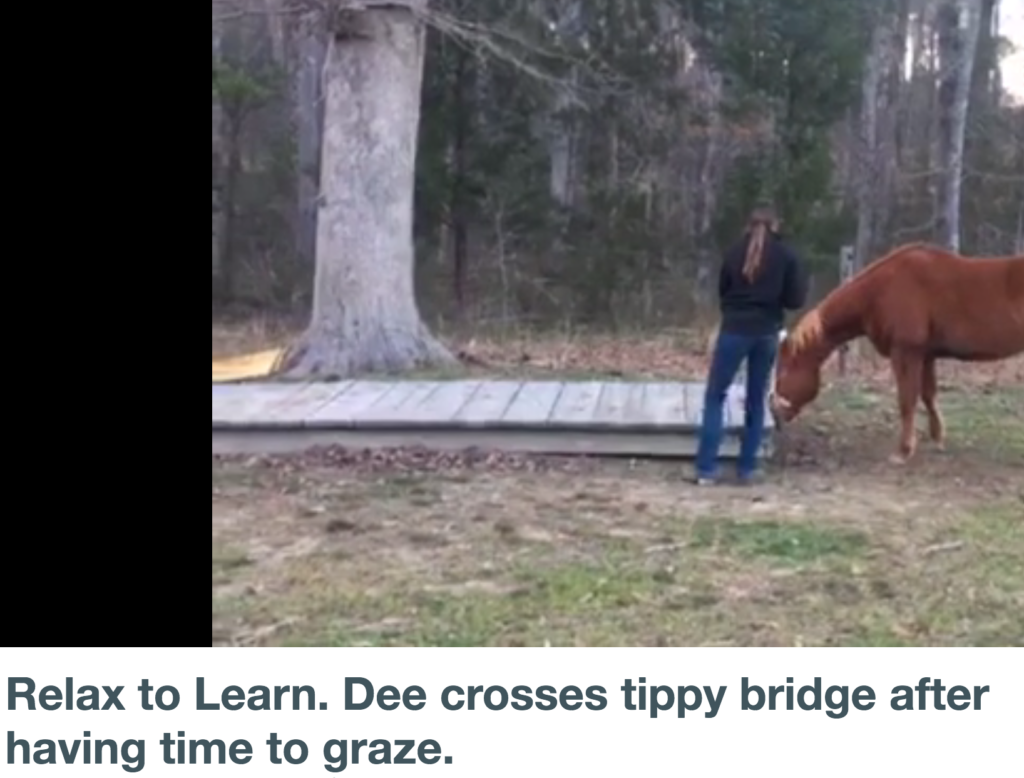

I had another insight when working with my mare, Dee. For a long time, she has struggled with crossing Bar T Ranch’s tippy bridge obstacle.

Following the seminar, I had a new strategy to try:

I let Dee graze by the bridge for a while. She was able to be comfortable near it and engage her parasympathetic nervous system (“Rest and Digest”). She eyed the bridge while she chewed grass and hung out. Then I asked her to cross it. Success!

Dr. Peters reminded me that it’s not really about the food. “It is about managing where the horse is within its nervous system and less about the food. We are just using the food to activate the parasympathetic nervous system,” said Peters.

Now I’m realizing that I have no reason to hold on to old beliefs and habits that don’t serve the horse. Learning new things can challenge my belief system. This is good! I urge you to be a scientist and a horseman. Use your eyes, ears, and mind always. Don’t just believe what you’re told: think, compare, observe, and experiment. You owe it to your horse.

Skinner heads to Maine next month to teach lessons.

Watch what happens after Dee is allowed to graze before tackling an obstacle.

As a life time trainer I also like learning new things. I spend my summers up in the mountains at a horse camp. Every spring I have to get really firm to get across a certain bridge. Once it’s done its good for the whole summer. I’m going to get off I let him eat the lush grasses around the bridge. Looking forward to this experience. Tnk you.

Great work. I work with dogs this way. ie, putting cooked liver onto an object they are afraid of. We r altering their association with something, laying down a pathway in their brain labeled ( things that look like this) of course seeing something and hearing something very loud is totally different and requires the loud noise and distance. I’m sure new neural pathways can be laid in a horses brain, it’s just about being very consistent. With dogs there is always that fine line between creating a good association and rewarding a fearful response. Is this the same with horses? Thanks so much . Anthea