In this article on the complicated nature of California’s wildfire problem, reporter Quinn Norton talks about technical debt. She writes, “technical debt is the shortcuts and trade-offs engineers use to get something done either cheaper or in less time, which inevitably creates the need to fix systems later, often at great cost or difficulty.”

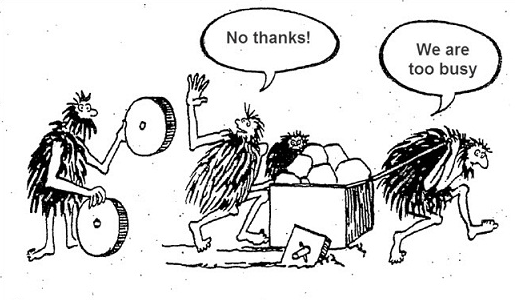

Haste, waste. An illustration of technical debt

Sound familiar? Horsemanship debt happens, too. What kind of debt are you incurring? When and how will this debt come due?

Here are examples of debt coming due in the greater world:

- Poor forest management contributes to the increase in massive wildfires.

- Poor home building leads to expensive heating and repeated maintenance.

- Neglecting your physical and mental well-being leads to health problems.

Debt is what happens when you overlook small steps on the way to a bigger goal. Debt happens when you focus too narrowly on the task at hand. Think, “blinders on.”

Jolene

Debt happens when you rush through steps in the name of accomplishing what you told yourself you wanted to accomplish on that day, week, or given season.

I’ve been guilty of technical debt with at least two equines: I wanted to get to riding Jolene so badly, that I rushed the process. At the time, I reasoned with myself. “I got this,” I said with nervous energy. The first two wrecks should have been warning enough. It took a more serious one for me to pay attention to what my mule had telling me for months. Read more about that here.

More recently, I’ve been working with Barry, a rescued Tennessee Walker who endured harsh handling and neglect for years before I acquired him. After lots of ground work and round pen work, I started trail riding with him. Then a bolting incident made me realize my methods were wrong. I would need a different and more patient approach.

In both cases, I tried at first to rationalize my motives and missteps. I tried to justify what I’d done and tell myself that the incidents were just flukes and that my horsemanship was sound.

But, as Norton writes, “skipping past bargaining and anger and even depression, all the way to acceptance of this new reality, and getting to work, is the best we can do.”

Barry

The faster I can accept my missteps, the faster I can address the real situation. It is a logistical, skill-based process, but it is also an emotional one which requires shedding one’s ego and preconceived notions.

The more quickly I’m able to address the real picture, the better I will be at getting back to work. In this case – as in so many with our horses – it will involve going more slowly and thoroughly.

Maddy, I sure would benefit from Barry’s story too, if you care to share the details. I imagine we can all recognize ourselves in your article. The more nakedly we can see our motives and mis-steps, the better we are as humans and horse trainers.

Hi Betsy, Thanks for your comment. Unfortunately, I think it’d take a few thousands words to unroll the Barry story. Suffice to say, I learned that I need to work through, not around, his baggage and nervousness. Thanks again!