Something tragic and something fun happened this month.

Something tragic and something fun happened this month.

First the tragic:

I’ve been riding my new, nervous horse, Barry. We’re making wonderful progress. But as summer heats up, I’ve noticed my saddle pad leaving sweaty, uneven marks on his back. The marks are indicative of poor saddle fit.

I’ve tried to deny it and to comfort myself with these notions:

- it’s an otherwise well-made saddle that should be comfortable for him, even if it is doesn’t fit him perfectly.

- He’s big and I’m not so heavy as to cause him discomfort.

- He doesn’t do anything obvious to indicate that he’s uncomfortable.

Two pivotal developments tilted me towards a reckoning:

My friend and chiropractor, Kathy Klix, visited Barry and she noted how sore his withers were. Given that he’s completely sound, with good musculature and healthy feet, saddle fit got the pointy finger.

I contacted Elaine Welland at Western Sky Saddlery in Carstairs, Alberta. Over the course of several days, she reviewed images of Barry with and without my saddle. I even sent her images after a sweaty ride.

“I know exactly what’s happening,” she said by phone.

Dr. Kathy Klix

Basically, I’ve been using saddles that were built for horses with straighter (flatter) backs. Barry has high withers and a back that angles a bit up towards his butt. He needs a saddle with more rock in it and perhaps a pad with greater contour.

I’m in the process of acquiring a better saddle for this lovely gelding.

Next, the fun:

While bemoaning my wrongness and my wallet (good saddles are expensive), two features on error had me practically celebrating the moment.

First, Shankar Vedantam, host of Hidden Brain, talked about the psychology of false beliefs. He interviewed researchers who study confirmation bias.

What is confirmation bias?

It’s our tendency to embrace data that supports what we already believe and reject information that doesn’t confirm what we already believe.

As Vedantam said, “As we move through the world, quickly sifting through news headlines and the flow of information on social media, confirmation bias gives us a feeling of stability.”

Added his guest, Tali Sharot, author of The Influential Mind: “However, having confirmation bias also means that it’s really hard to change false beliefs. So if someone holds a belief very strongly, but it is a false belief, it’s very hard to change it with data.”

Barry needed a saddle with more rock, noted Elaine from Western Sky Saddlery

Vedenatam added, “We tend to accept information from people we trust, and once we do, we are resistant to changing our minds. Most of us think we arrive at our beliefs through logic and reason. [But] there are forces that may matter even more – our feelings, our social networks and our relationships with other people.”

Regarding me, my horse, and the ill-fitting saddle: I really wanted to believe that my saddle would work and that Barry would be fine with it. Coming to terms with my wrongness was a process involving my acceptance of new information which was delivered in a variety of gentle ways. It was a positive blend of reason and relationships.

I also reckoned that my ego was interfering with what could have been a quicker, kinder conclusion about poor saddle fit.

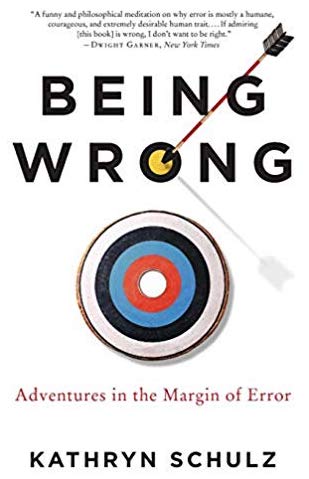

“Being Wrong” an intellectual romp of a book by Kathryn Schulz, helped shift my perspective.

She writes in her introduction: “I’m interested in error as an idea and as an experience: in how we think about being wrong and how we feel about it….In daily life, we use ‘wrong’ to refer to both error and iniquity: it is wrong to think that the earth is flat, and it is also wrong to push your little brother down the stairs.”

Indeed, I had been feeling right about my old saddle and right about my being a good horse person; the two sentiments stuck together like glue. Humans, writes Schulz, “have a long history of associating error with evil – and, conversely, rightness with righteousness. “

Thankfully, I got over myself and started embracing what I was seeing and hearing from people I trust. In the end, with a new saddle on its way, the experience felt downright uplifting. The process was humiliating and illuminating at the same time.

I laughed went I read Schulz’s words:

I laughed went I read Schulz’s words:

“There is no experience of being wrong. There is an experience of realizing that we are wrong, of course. …recognizing our mistakes can be shocking, confusing, funny, embarrassing, traumatic, pleasurable, illuminating, and life-altering…But by definition, there can’t be any particular feeling associated with simply being wrong. Indeed, the whole reason it’s possible to be wrong is that, while it is happening, you are oblivious to it. When you are simply going about your business in a state you will later decide was delusional, you have no idea of it whatsoever. You are like the coyote in the Road Runner cartoons, after he has gone off the cliff but before he has looked down. Literally in his case and figuratively in yours, you are already in trouble when you feel like you’re still on solid ground. …It does feel like something to be wrong. It feels like being right.”

“Whatever falsehoods each of us currently believes are necessarily invisible to us. As soon as we know that we are wrong, we aren’t wrong anymore, since to recognize a belief as false is to stop believing it. Thus we can only say, ‘I was wrong.’ …We can be wrong, or we can know it, but we can’t do both at the same time. “