Editor’s Note: Maddy Butcher presented with Connie Crawford and Kari Weil at Brown University’s Re-Examining Conservation. The symposium’s equine-related presentation was title “Horse Sense.”

Maddy Butcher writes:

The horse, as a species, can be so mystical and mythic and magical. It’s easy to get lost in ideas around how we connect with equus caballus. We can spend a lot of time in our heads and with our heads in books, can’t we? Indeed, my work as a journalist and a conference director and a horsewoman all stems from an idea that Dr. Frans De Waal, a primatologist at Emory University, put forth years ago: that in order to do right by another species, we must know it intimately.

The horse, as a species, can be so mystical and mythic and magical. It’s easy to get lost in ideas around how we connect with equus caballus. We can spend a lot of time in our heads and with our heads in books, can’t we? Indeed, my work as a journalist and a conference director and a horsewoman all stems from an idea that Dr. Frans De Waal, a primatologist at Emory University, put forth years ago: that in order to do right by another species, we must know it intimately.

I think that this gathering is about doing right for this planet’s other species. So I thought I’d describe a bit about what that might look like for horses.

It means learning about anatomy, digestion, physiology, neuroscience, and herd dynamics. It means learning about management, biomechanics, conditioning, and nutrition. It means getting dirty. It means learning how to trailer horses, how to tie a quick release knot, and learning that when it’s dark and you still have a few miles to go, that you drop the reins and let your horse take you home because he savvys the way better than you.

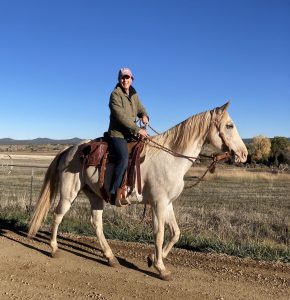

Knowing horses intimately, I’ve found, involves work that is physical and ultimately intuitive. Virtually all of it is away from my desk and out of my scholarly head. It involves a lot of fencesitting and a lot of time in the saddle.

Knowing horses intimately, I’ve found, involves work that is physical and ultimately intuitive. Virtually all of it is away from my desk and out of my scholarly head. It involves a lot of fencesitting and a lot of time in the saddle.

A horseman I know told me years ago that watching someone train a horse is like watching paint dry for some people. Or maybe, it would be like watching a baseball game for someone who doesn’t know baseball, in which there is so much going on at a very subtle level that for an untrained observer, it would be dull and boring.

Horse work and horses, I think Connie and Kari would agree with me here, are not dull and boring.

There are about four million horses in the U.S. now. They exist in our fast-moving society in which we fly in planes. We get places quickly. We accomplish tasks quickly. We have apps and drugs and clubs for doing things and getting what we want. Yet, we are not necessarily healthier and happier than we were 100 or 200 years ago. Research shows what we’ve been shedding is valuable, even essential to our well-being.

Time outside. Time with animals. They are key factors in crafting a vibrant life. And, not surprisingly, these things have everything to do with lives with horses.

Time outside. Time with animals. They are key factors in crafting a vibrant life. And, not surprisingly, these things have everything to do with lives with horses.

Studies show that horses may be the most effective “feel good” animals. Indeed, the number of horse-related therapeutic centers is steadily increasing. This growing community is helping to successfully repurpose horses from beasts of Burden to Beasts of Being.

What we horse owners know as horse time is rebranded here as equine therapy, equine-assisted learning, equine-facilitated therapy, and so on. These entities have discovered what we riders and owners have always known, but perhaps taken for granted: Hanging around horses makes us feel good.

There are two reasons why this is so:

Imagine you’re standing by a horse, with one arm draped over its back. Listen to its breathing. Place your face in its mane and smell that sweet, musky scent. Feel heat radiating from its thousand-pound body. Put your ear to its belly and listen to the incessant gurgling. Watch the eyes and ears. Those ears swivel independently; one might be on you, while the other might point toward the wind. Those eyes are the biggest in the mammalian world and the horses’ field of vision is expansive, about 300 degrees.

Imagine you’re standing by a horse, with one arm draped over its back. Listen to its breathing. Place your face in its mane and smell that sweet, musky scent. Feel heat radiating from its thousand-pound body. Put your ear to its belly and listen to the incessant gurgling. Watch the eyes and ears. Those ears swivel independently; one might be on you, while the other might point toward the wind. Those eyes are the biggest in the mammalian world and the horses’ field of vision is expansive, about 300 degrees.

If you let yourself, it’s easy to become immersed in the horse’s presence. And that’s the point. The immersion is therapeutic.

The second explanation for what horses offer us is that engaging with them for any prolonged period of time becomes an earned partnership. With horses, we learn about respect, trust, consistency, and boundaries. It’s a relationship that’s challenging to obtain and maintain.

It’s very much a two-way deal and, therefore, has great value.

These qualities of horse time make it more effective than gardening, listening to music, or scores of other activities marketed to address one’s well-being. That recognition and the growth of horses as effective therapists is not unlike that moment, 5,500 years ago, when some folks in what’s now known as Kazakhstan considered domestication and the riding of horses for the first time.

But when we say we want horses in our world and in our future worlds, what does that look like? How can we make it worth their while? What can we offer other species?

But when we say we want horses in our world and in our future worlds, what does that look like? How can we make it worth their while? What can we offer other species?

I think these are questions we’re considering with this symposium.

As I said, we owe it to horses to know them intimately. And we should use that knowledge to set them up for success in every way. Practically speaking here are a few examples of what that looks like:

We’re not putting them in stalls. We’re not isolating them. We’re not giving them grain or feeding them three meals a day. In other words, we’re not anthropomorphizing. We’re not thinking about what’s best for us humans. Since we know them intimately, we should know how treat them like horses. Horses need to be in a herd. They need to move and graze most of the day and night. Freedom, friends, and forage are priorities for equus caballus.

Since they are non-verbal, we need to study what they’re saying with their bodies. They respond well, for instance, to negative reinforcement, also known in horse circles as ‘pressure and release.’ This is like me stepping into your space and you taking a back step. This is how horses move each other – you can see that in some of the videos Connie has featured. And it’s how we can effectively work with them.

When my friend said that good horse training is like watching paint dry, it’s because those trainers have learned to be very quiet and subtle with their cues. So the pressure for instance, might be an inch of lean towards the horse and the release might happen as the horse thinks about changing direction. We might notice a horse’s shift in mindset by way of an eye blink or a softening of its jaw. The more you know, the more you see in what is a fascinating cross-species dance. The more you know, the better you can get along with these thousand-pound animals and the better you can advocate for them.

The book The Body Keeps the Score by Dr. Bessel Van Der Kolk was instrumental in helping me understand how trauma and stress can be stored and manifested in our bodies. So, too, with horses. It may not be surprising for you to hear that lots of horses have traumas and stresses of their own because of injuries, physical and mental, that for the most part humans have inflicted on them. They can tell us a lot about how they’re doing if we are observant and listen and if we know what to notice and what to pay attention to – how they behave, how they move, how they react to us. Healing can happen for them, too.

Another important issue, when considering our future with horses is what we bring to them with each and every interaction. What do they think of us? How do they consider us?

To answer these questions, I think us humans need to know ourselves intimately.

We are finding that the most successful horse-human connections are made by owners and riders who recognize horses’ sensitivities and are supremely mindful of what they, the humans, bring to the barn or the arena on any given day. Are you stressed? Nervous? Angry? Braced? Unconfident? Horses feel that from a hundred yards away.

I believe that when we do the hard work of being cognizant of our energies and our emotions, then we can more effectively communicate across species. When we listen more and talk less, we can more effectively communicate across species. It’s often a matter of letting go of our humanness, and of our busy brains, to get to what matters.

These are some of the reasons why I think horse work is so fascinating and multi-faceted. This is why they deserve to be part of the conversation. Having a handle on our part / impact of any inter-species interaction has everything to do with the conservation and perpetuation of our fellow animals on this planet.

Well stated! I’ll add that horses respond well to positive reinforcement as well and if they have a history of trauma, oft times better. And although they are equines, lest anyone be confused and I’ve trained a few, donkeys don’t respond well to pressure. They do much better with R+ And more time. With either pressure or positive reinforcement, time to process is a huge component. As you mention we are all used to instant everything. Having to slow down and go on “horse time” is another huge benefit for us humans. Sadly this critical piece often gets lost, to the horse’s detriment when they go to a trainer for 30 or 60 days for what really takes a year to learn.

In my eyes, you capture the essence of the horse in our lives.

They give more than they get.

Horses and horse people are fortunate to have you in our lives.

Thank you Maddie–

You’re very kind, Carrie. Thanks!