By Maddy Butcher

Most of us learn about wild horses through the polarized lenses of ranchers, who want them gone, and activists, who want them to run free. Rarely is light  cast between the two extremes. Yet, as with any highly politicized issue, somewhere in the middle is where you’ll discover a closer version of reality and get a better understanding of how things might move forward.

cast between the two extremes. Yet, as with any highly politicized issue, somewhere in the middle is where you’ll discover a closer version of reality and get a better understanding of how things might move forward.

At the Impact of the Horse event and the Bureau of Land Management’s Delta, UT, holding facility, we visited with officials and horsemen to gain a better sense of the condition, operation and future prospects for the horses and those charged with managing them.

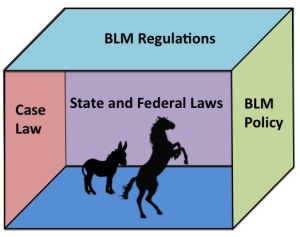

Gus Warr, head of the BLM’s Utah Wild Horse and Burro program, uses the image of a box to illustrate the unnatural state of mustang affairs.

It’s walled by BLM policy, BLM regulations, case law (interpreted by myriad judges over four decades), and other state and federal laws.

It’s walled by BLM policy, BLM regulations, case law (interpreted by myriad judges over four decades), and other state and federal laws.

Now take these walls and move them up, down, left, and right as policies shift and judgments are handed down. Shake it with emotion, partisanship, media and social media. The result is a frustrating, complicated scenario that no one calls ideal and many label fundamentally flawed. Horses are the subjects and victims.

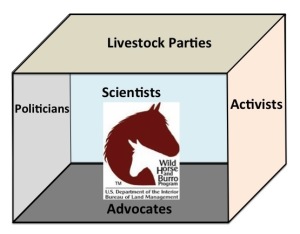

The BLM itself is also in a box. This one is walled by the stakeholders: activists, ranchers, politicians, scientists, and advocates.

The agency, since 1971 charged with managing the animals according to the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, is constantly challenged and constrained by these stakeholders. Often the parties share less common ground than dressage queens and bronc riders. Imagine then, these walls being magnetically opposed.

The agency, since 1971 charged with managing the animals according to the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, is constantly challenged and constrained by these stakeholders. Often the parties share less common ground than dressage queens and bronc riders. Imagine then, these walls being magnetically opposed.

To date, Warr’s job description involves far more than simply caring for the horses and burros. In recent years, the 23-year BLM program veteran has dealt with horses being shot on the range, bomb threats, illegal chases, and violent harassment. Click here to read about this year’s Interstate 15 incident.

To make matters worse (for the BLM and for the horses), hay costs are high, the equine market is down, and society is shifting away from hobbies and professions with horses. Twenty years ago, Americans adopted 8-10 thousand mustangs annually. Now, barely 2,000 leave the facilities for private homes each year.

“It’s such a hot button issue,” said Warr. “In my mind, it’s almost bigger than immigration. It’s emotionally challenging and politically challenging. It’s a very complicated program.”

Read more about the science and how we got here.

At the Delta facility, facilities manager Heath Weber showed us around. There are about 200 horses separated into groups of 10 to 30 and held in large paddocks. There are separate paddocks for yearlings, mares, burros, geldings as well as a space allocated for a few horses in need of medical treatment.

They move freely, sometimes napping in the sun, sometimes gathering in threes and fours, sometimes grazing from the hay trough. Nearly all of them watch as we pass. Many approach and tentatively accept a rub.

When horses need treatment, they are moved through a simple system of gates and panels to a

containment space inspired by Temple Grandin (a pioneer in humane livestock handling. Read more about her here.) Horses and burros are then moved into a squeeze shoot to receive freeze marks (neck brands made with liquid nitrogen), hoof trims, and other treatments before being returned to their pens.

Weber showed us a group of geldings from the Sulphur Herd Management Area. It’s one of the few herds to gain international attention for its supposed lineage to original Spanish colonial horses. As we spoke, potential Internet adopters were high-bidding for the most colorful of the bunch.

It’s a strategy that has its drawbacks. “You can get a colorful horse, but you may get a whole lot of crazy, too. First off, I look for the calm, level-headed ones,” said Weber.

Weber has three mustangs at home. He’s competed in the Extreme Mustang Makeover and his brother, Tate, is a TIP trainer.

To my eye, the Sulphurs looked a lot like all the other mustangs and not too different from some light, petite, ranch horses I’ve seen lately. That’s what can happen when loose horses breed over large territories and many generations. Who really knows what you’re getting?

Weber pointed out a distinctive, heavier-set Sulphur. “We were wondering if he might be a Haflinger,” he chuckled. Read about domestic horses turned out to the range.

Ideally, said BLM officials, they’d like to gather no more than they can adopt each year and limit reproduction in existing HMAs through contraceptive darting and other reproduction reduction efforts.

That strategy still leaves unaddressed those tens of thousands of horses and burros in long-term holding facilities. That “bigger elephant in the room” said Warr, is still problematic and will remain so until policies change and stakeholders compromise.